In the Chalcolithic period of Cyprus, around 3900 to 2500 BC, women likely held key roles as priestesses or ritual leaders in communities like those near what would later become Enkomi. These figures guided ceremonies focused on fertility, birth, and the emerging magic of metallurgy, acting as bridges between daily life and unseen forces. Their story uncovers a time when religion was woven into survival, leaving us with intriguing artifacts that hint at powerful female authority in ancient Cypriot society.

Unveiling an Ancient Spiritual World

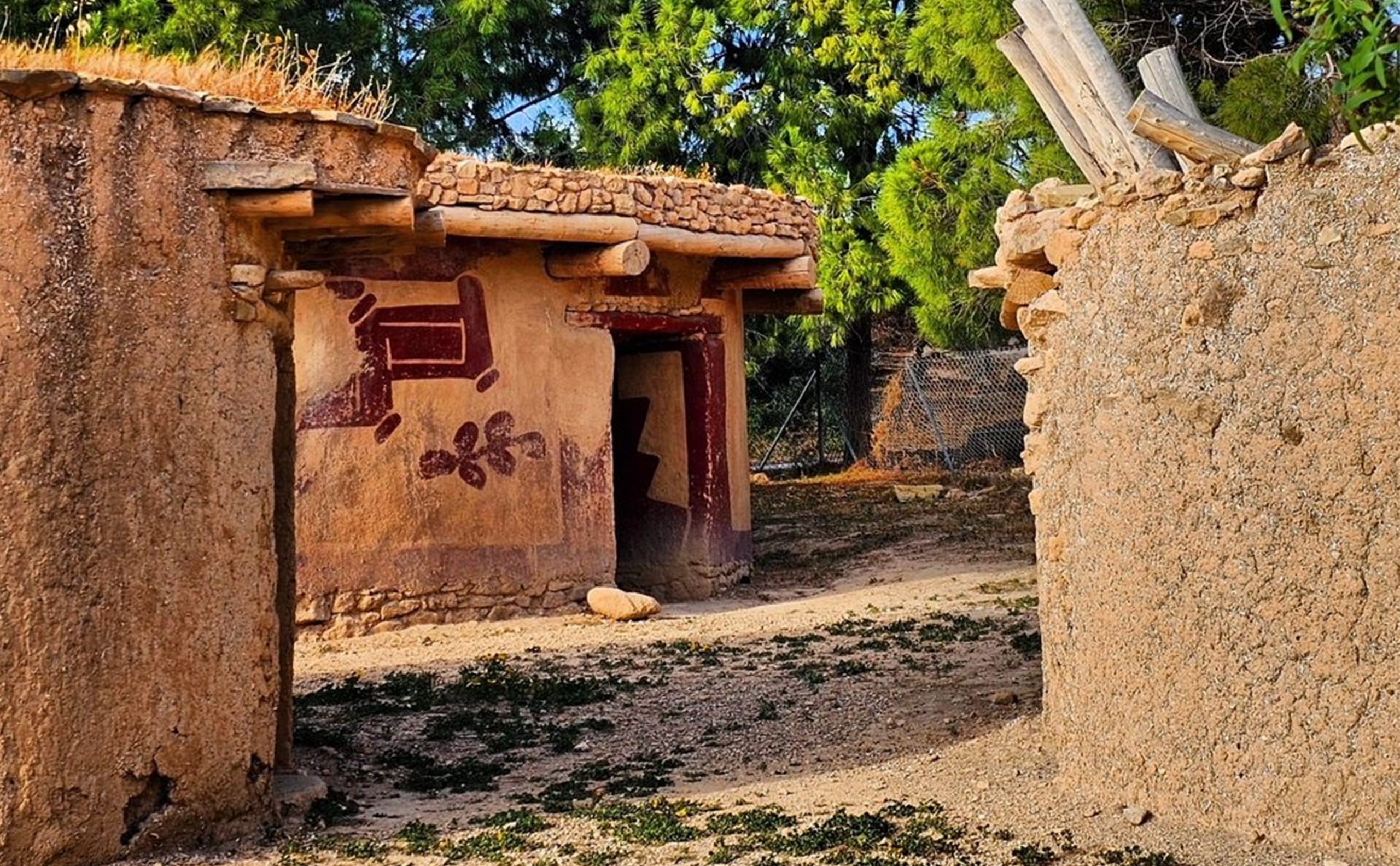

Step back to a Cyprus without cities, kings, or written words – a landscape of scattered villages where life hung on the whims of nature. This was the Chalcolithic era, a bridge between the Stone Age and Bronze Age, when people first experimented with copper tools and settled into larger groups.

Communities clustered around fertile valleys and rivers, like those in the Paphos region or near the eastern coast where Enkomi would later rise. Religion wasn’t separate from daily grind; it was a toolkit for dealing with births, harvests, and deaths. Women, tied closely to life’s cycles through childbearing and caregiving, emerged as natural leaders in these rituals.

Though we don’t have names or titles, artifacts suggest priestesses – knowledgeable women who orchestrated ceremonies to keep balance in an unpredictable world.

Roots in a Changing Island

The Chalcolithic kicked off around 3900 BC, as Cypriots shifted from hunting-gathering to farming and herding, taming deer, sheep, and pigs while growing barley and lentils. Sites like Kissonerga-Mosphilia near Paphos reveal early villages with round houses, storage pits, and communal spaces.

By 3500 BC, copper smelting appeared – a game-changer pulled from Troodos ores, turning rocks into tools like awls and hooks. This tech boom brought trade with Anatolia and the Levant, but also risks like failed experiments or fires.

Amid this, spiritual practices evolved from Neolithic roots, focusing on fertility to combat high infant death rates (up to 50% in some digs). Enkomi itself enters later, in the Bronze Age around 1600 BC, but its area shows earlier Chalcolithic traces, with continuity in burial customs and symbols.

Myths of later goddesses like Aphrodite might echo these early female figures, blending local traditions with incoming ideas.

The Essence of These Ritual Leaders

Imagine a Chalcolithic priestess: not a robed oracle in a temple, but a community elder with hands stained from clay and herbs, her neck hung with picrolite pendants. These women weren’t appointed by decree; their power came from experience – understanding menstrual cycles, pregnancies, and the earth’s rhythms.

Artifacts show female forms dominating: exaggerated hips, breasts, and bellies symbolizing nurture and renewal. At Souskiou-Vathyrkakas cemetery, uneven grave goods suggest women held sway in rituals, perhaps leading initiations or healings.

Their roles balanced life and death, invoking forces for bountiful fields or safe births. Unlike later male-dominated cults, this era’s spirituality felt intimate, tied to the body and land, with priestesses as mediators who kept social harmony amid growing villages.

Fascinating Glimpses from the Past

The Chalcolithic hides quirky secrets that bring these priestesses to life.

● Take the “Lady of Lemba,” a 36cm limestone statue from Lemba-Lakkous, dated to 3500 BC – her long neck, wide hips, and stylized face scream fertility icon, possibly a stand-in for a priestess in rituals.

● Worn picrolite cruciform pendants, shaped like crosses with female features, were likely amulets worn by women during labor; one from Pomos, around 3000 BC, has arms outstretched as if blessing or birthing.

● At Kissonerga-Mosphilia, a pit hoard held mutilated figurines stacked with shells and tools – a “deconsecration” rite, perhaps led by priestesses to mark a village’s end or a crisis resolved.

● Copper spirals in graves hint at metallurgy’s magic; early smiths might have sought priestess blessings to tame fire, seeing smelting as a birth-like process.

● Some figurines show birth scenes on stools, complete with emerging babies – like ancient birthing manuals, used in initiations where priestesses taught young women life’s mysteries.

Deeper Insights into Rituals and Society

Peel away more layers, and you see how priestesses wove into society’s fabric. Figurines weren’t idols for worship; they were tools in hands-on rites.

At Erimi-Pamboula, vulva-shaped pendants of terracotta suggest fertility charms, perhaps dangled in dances to invoke rain or growth. Rituals happened in open pits or homes, not grand structures – think communal fires where priestesses timed offerings to seasons, using red-painted lattices on figures to mimic tattoos or blood.

Metallurgy added awe: early copper from sites like Mylouthkia was rare, non-local (some from Anatolia), so priestesses might have ritualized its extraction, linking earth’s “womb” to human birth.

Socially, emerging hierarchies appear – larger houses at Kissonerga hint at elite families, with priestesses from them holding sway. Burials evolved too: from simple pits to chambers with malachite cosmetics in shells, suggesting makeup rituals for the afterlife.

Influences from Yarmoukian Levant or Beycesultan Anatolia blended in, but Cyprus kept its flavor – female-centric, focused on continuity amid small populations (maybe 1000 per site). These women weren’t rulers, but their knowledge ensured survival, challenging ideas of “primitive” societies.

Their Legacy in Modern Cyprus

Today, these Chalcolithic priestesses whisper through Cyprus’s cultural veins, influencing how the island views women, nature, and heritage. In a place dubbed Aphrodite’s birthplace, their fertility focus foreshadows the goddess’s cult, with echoes in festivals like Anthestiria, where flowers symbolize renewal.

Amid gender equality strides, artifacts inspire artists – think sculptures reimagining the Lemba Lady as symbols of empowerment. Archaeologically, they’re a call to preserve: climate threats erode sites like Kissonerga, but UNESCO pushes protection, tying ancient rites to eco-awareness.

Locals in Paphos villages share folklore of “earth mothers,” blending old beliefs with Orthodox saints who oversee births. In divided Cyprus, these figures unite – shared roots predating borders, reminding everyone of women’s historical strength in fostering community resilience.

Discovering the Echoes Firsthand

You can’t visit a “priestess temple,” but Cyprus brims with spots to feel their presence.

Head to the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia, where halls showcase figurines like the Pomos Idol – free on weekends, with labels explaining rituals (pack curiosity; audio guides help).

For outdoors, explore Lemba Archaeological Project near Paphos: guided tours (book via local sites, €10) wander village remnants, imagining priestess-led ceremonies. Kissonerga-Mosphilia’s digs are fenced but viewable from paths – spring’s best, with wildflowers evoking fertility rites.

Wear sturdy shoes for uneven ground; summer heat hits hard, so mornings rule. Combine with Paphos Archaeological Park for later contrasts, or hike Troodos for picrolite sources. No fees for trails, but respect signs – these are living history.

Safety-wise, roads wind; drive slow, and if digging deeper, join workshops recreating clay figures. It’s immersive: touch replicas, sense the ancient balance these women maintained.

A Lasting Tribute to Ancient Wisdom

In the end, the Chalcolithic priestesses of Enkomi and beyond deserve our attention because they reveal Cyprus’s soul – a cradle where women shaped beliefs that sustained life through change.

They turned uncertainty into ritual, fertility into power, and simple clay into symbols of endurance. Knowing them enriches the island’s story: a tapestry of innovation, from early copper to cultural blends, all rooted in human experience.

Whether gazing at a figurine’s curves or walking ancient grounds, they remind us that true authority often blooms from care and connection. In our divided, fast world, their legacy calls us to honor cycles – of birth, growth, and renewal – keeping Cyprus’s ancient heartbeat alive.

English

English Greek

Greek German

German Russian

Russian